There is an assumption that space is an infinite realm. Yet while space may seem vast, Earth’s orbit is decidedly less spacious, and the orbital range for satellites is both limited and increasingly crowded.

All satellites are confined to just a few orbits. Geosynchronous orbit satellites (GEO) follow Earth’s rotation from an altitude of about 22,000 miles, thereby appearing stationary. Low-earth orbit satellites (LEO) fly close to Earth at an altitude up to around 1,000 miles, which makes them faster. Medium Earth orbit satellites (MEO) fly at an altitude between 6,000 and 12,000 miles. Geostationary polar orbits are helpful for monitoring activities, including collecting weather intelligence, studying environmental changes, or responding during an emergency.

Space domain awareness (SDA) is crucial to maintain daily life as we know it. Beyond individual convenience of Global Positioning System (GPS)-powered maps for navigation, the data from GPS satellites is used for mission critical warfighting activities, Internet connectivity, farming, construction, mining, power grids, postal services, humanitarian efforts, weather forecasting, and much more.

“It took a long time to get to where we’re at so it’s important that we’re able to protect those assets and ensure that they’re able to provide the same capabilities people depend on from a day to day perspective,” said Matt R., Senior Director of Mission Ground Systems.

Tracking and cataloguing space objects is critical to avoiding accidental collisions and defending against adversarial activities in space. Even a small sliver of space debris can cause consequential damage due to its high velocity. The more satellites that are launched into orbit, the more coordination will be needed to ensure safety. Over the course of his fourteen years working as Peraton’s Thule Greenland Station manager, George G. has noticed the orbits getting crowded, “but it has been maintainable so far,” he said.

Every day, Peraton’s orbital analysts calculate the location and trajectory of customer satellites for both situational awareness and defense purposes in order to ensure mission success. They perform orbit determination, which calculates the location of the satellite or object to make sure satellites don’t hit each other or any space debris, and conjunction assessments, which check space objects against a catalog and add new entries if there is not a match. Orbital analysts also help maintain the life of their satellites through health checks and planning maneuvers. “If we do our jobs, then nobody knows we exist,” said Christine M., Program Manager of Orbital Analysis Support (OAS). “We can’t point to our work because if we’re successful, nothing happens.”

A collision could be catastrophic for two reasons. First, it could reduce the availability of information that so many people rely on for actions ranging from simple Internet tasks to complex military missions. Second, a collision would create uncontrolled debris fields that could then increase the chances of additional satellites being damaged or destroyed.

“We need to be able to give those who are looking to put more capabilities up into orbit the assurance that if they go through that process and make that investment, technologically as well as monetarily, that it won’t be like putting a carton of eggs on a highway and hoping it survives through rush hour,” said Matt. The key to satellite sustainability is data. Peraton’s Special Space Systems division has been working on technological solutions for using data more effectively: evolving telemetry, tracking, and control (TT&C) to protect, share, and more efficiently analyze the information that comes down from satellites for decision-making.

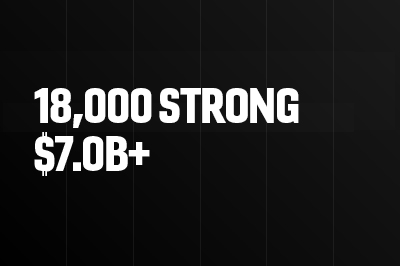

Peraton has always been at the forefront of space resiliency. Peraton employees provide satellite operations, maintenance, systems architecture, and systems engineering to support critical missions from beginning to end.